A Crisis of Time: My Reflection on the Murder of Joe Mcknight

Read MoreOriginally Published At Patheos

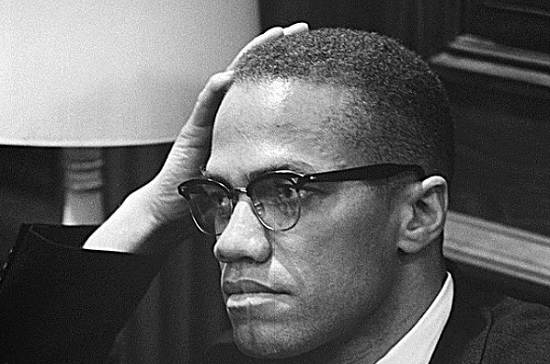

What would Malcolm do this Black History Month?

“Yo this is the Blackest history month ever!” I told my wife, Imani, after she told me that this year was a leap year. We both laughed shamelessly at each other. Black History Month was coming to a close with a screeching halt. This Black History Month has been one for the record books for me: Saturday, February 20th took an ordinary Black History Month into another galaxy, a black hole even.

It all began with Malcolm X, or el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz.

I’m not a scholar of Islam. When I’m asked to speak at Muslim venues, a million thoughts race through my mind about what I should or shouldn’t say. Maneuvering through YouTube treatises on why certain Muslim public figures are leading people astray has now become an art form for me. Somehow, one way or another, I know that one day I’m going to be the subject of the hour-long dragging sessions in the name of “banishing falsehood” from the land.

But last Saturday I showed up, taking a chance. My lecture was on the intersections of Islamophobia and Black Lives Matter, two topics that have heroic amounts of research, op-eds and witty tweets locked and loaded, should you need to take a crash course in staying “Woke.” Ten minutes late, I blasted through the parking gate throwing my car furiously into park. My escort greeted and showed me to where I and four others would be speaking.

We winded through the steps down to the basement level auditorium. It was packed to the rim, and now the anxiety kicked in a bit more. I took the only open seat among the panelists. I greeted both of them and in approximately three minutes, the program started.

After Imam Daud Haqq concluded the first lecture, the brother I was seated next to, took the podium. The events co-organizer introduced him as Muhammad Jabir, the son of Hisham Jabir, the man responsible for performing the janaaza (funeral prayer) of Shabazz’s body secretly. Jabir’s first words, “Many people did not know Malcolm X like my father did,” rang like tower bells around the room. He went on to explain why.

From his father, Hesham Jabir’s, clandestine role in Shabazz’s funeral arrangements, to introducing a glimpse of the worldview Shabazz would inherit after his movements throughout the world — we all gained a piece of Shabazz through Jabir’s storytelling.

I was supposed to follow this political eulogy with a conversation that I had refined in every way possible by then. It took me 25 minutes to make the key points — otherization, profitable hatred, white supremacy — but I knew that what would have been game-changing was if I could possibly attempt to travel into the mind of Shabazz and offer what Shabazz’s instructions would be as a Black Muslim during Black History Month.

These were some of the thoughts I had:

Shabazz would first debunk all notions that Muslim is the new Black. He’d probably go as far as to say that the attempts to relegate oneself to this perceived status of subjugation likened to African Americans reflects nothing of the empathetic intelligence needed to vanguard the Islamic experience. Shabazz would also probably mangle this argument, citing the fact that in order to have a “new Black,” there has to be an old one.

I presume he’d then go on to say that since the death of Trayvon Martin and fast growth of the Black Lives Matter Movement, the “old” Black people are still seeing their way through this experience as best they know how. I believe Malcolm would apologize on the behalf of that rhetoric and sharply remind our communities that to be Black and Muslim right now in America is one of the foremost complicated situations to dwell in — detainment by TSA at airports are what stop and frisk looks like every hour in Black communities since the three decades of a national “drug war.”

Shabazz would make a mandate that every Muslim get registered to vote, not because it is a panacea to social illnesses faced here, but because the vote is a critical arm of the struggle. Shabazz would point to the legacy of Adam Clayton Powell to define exactly what having an unapologetic representative in political office looks like. He’d challenge all cities and states with majority Black representation to push for the same legislation was passed in Baltimore last month, enfranchising former felons, thus creating an entirely new voting bloc.

Shabazz would make an awesome cadre of events. He’d make February 25th, a national day of service dedicated to the mothers of children slain by killer cops in honor of Trayvon Martin. Every city would be required to have a parade, preferably ending on each city’s MLK Boulevard, raising their names. He’d commission the first annual Transnational Impact Awards for African Americans and Africans, who successfully conducted business and invested in African infrastructure.

Maybe he would host a national debate with Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders.

Tariq Touré

With passing of Supreme Court Justice Scalia, Shabazz would call President Barack Obama personally and tell him to make the Executive Order of appointing Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow, to replace Scalia. He’d then draft the proposal to end indiscriminate drone strikes and institute the first civilian drone review committee. And considering what Guantanamo Bay is guilty of as an institution, he’d call for its immediate shutdown.

This is what I was thinking, what I considered saying at the event.

But instead, I went on about how young Muslims have to see themselves as the leaders we’ve been waiting on. I discussed people like Kalief Browder, who was kidnapped in the form of an arrest when he was 16 on false charges and spent the equivalent of two years in solitary confinement. The crowd was engaged as I explained that the entertainment industry cashes in hand-over-fist by pushing anti-Muslim, anti-Black propaganda and that only by building systems will these structures be counter-acted.

I did my very best in 25 minutes to cover the subject matter assigned to me. After all, it is Black History Month.

I didn’t share my internal thoughts because I am sure that had El-Hajj Malik Shabazz been present — and I was an attendee — he would have encouraged something much more impactful than I could ever imagine.

Originally Published at Muslim Matters

3 Young African Muslims Shot Execution Style: Many Questions To Be Answered

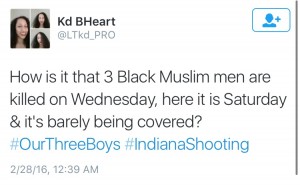

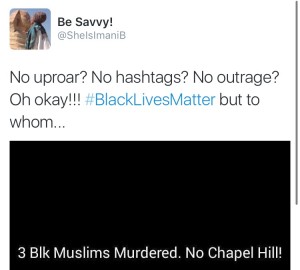

Fort Wayne Indiana was host to 3 execution style shootings in the past week. Law enforcement officials identified the bodies of Mohamed Taha Omar, 23, Adam K. Mekki, 20, and Muhannad A. Tairab, 17 on Wednesday in the evening to the house where 2 of the 3 young men lived on 800 East Lewis St. in Fort Wayne, Indiana. Appearing not to be gang related to the Fort Wayne police, motivations for this type of heinous act are completely unknown. Alex Rowe 23, who lives a few blocks from the house on East Lewis St. said, “Only two shootings happened since I moved over here in January. One was the day I moved in and another was a less than two weeks ago when a cop got shot.” The shootings have made four the total count for the year in Fort Wayne.

Just north of Indianapolis lives Eidi Mohamed, 20, a student at IUPI and employee for an interfaith organization who remembers all three of the Sudanese boys in middle school as “really into sports, specifically soccer.” “There are a few news channels here covering but it really isn't getting attention like the Chapel Hill shooting” he went on to say. Asked whether or not the area has a history of overt racism towards Blacks or Muslims Mohamed recalled, “I've always heard about racist things going on in Fort Wayne, parts of Fort Wayne have a lot of African Americans and African Immigrants.”

In a report from The Journal Gazette, Police Chief Garry Hamilton and Public Safety Director Rusty York both said, “We're pretty certain they weren't targeted due to that” after questions about religious implication of the killing and that the house was at that moment a “Party House.” According to The Journal Gazette, York also added about the execution style killing, “There could've been a disturbance in the house or an argument of some kind. We just don't know.”

Both Alex Rowe and Eidi Mohamed stated that outside of usual prejudice, this type of racial violence is unheard of. Mustafa Kedio father of Mohamed Taha commented, “Right now I can't say it's a hate crime” and “The Fort Wayne Police Sheriff reported that it wasn't in anyway related to any gang activity.” Kedio recalled just finding out recently that, “Taha had been out of college for the last two semesters because of not being able to pay and in search of work.” “I think he was ashamed to tell me, but I would have paid for him.” Kedio is a former cab driver of 13 years in Chicago who recently began a labor job at a company called JPI. He insisted “my boy and the other two have never been involved with gangs and they do not have one thing in any of their records.”

As the story develops it is apparent that it carries the same weight as the Chapel Hill Shooting that initiated the hashtag #OurThreeWinners. The social media campaign erupted virally transcending the internet with Steph Curry paying homage to the hate crime by wearing their names on his game sneakers. On February 10 2015, Deah Shaddy Barakat, Yusor Muhammad Abu-Salha, and Razan Muhammad Abu-Salha were murdered in the same exact fashion as the young men in Fort Wayne.

Ian Maxton, a student living miles away from Fort Wayne agreed that it is “a very diverse yet highly segregated place.” “We mostly have robberies gone wrong, jealous lovers, and occasionally gang-related shoot-outs in the city. Never, to my knowledge, anything like this,” Maxton continued. Police officials are now working to attain details to a story that has many potential threads running through it.

National media has yet to begin to pry into exactly what has happened but Social Media is asking for a sizable amount of answers.

Inna lilahi wa inna ilayhi rajioon.